Northup and O'Brien, a Winston-Salem firm that encompassed architects Willard Close Northup, Leet O'Brien, and after 1927, Luther Lashmit, was one of the most prolific and distinguished architectural firms in North Carolina during the first half of the 20th century. The firm offered a full range of architectural possibilities for the urbanizing state, and its founders and members led in the establishment and promotion of the architectural profession. During their period of practice, their home base of Winston-Salem was the wealthiest city in the state, and the firm gained and kept as clients many of the leading industrialists of the city, while their field of commissions also extended throughout much of North Carolina. Their work encompassed myriad revival styles--including their distinctive local "Salem Revival" style originated by Northup--as well as new trends in modernism. The firm found remunerative and regular work in planning public schools, universities, and health facilities according to standards of the day, while also designing sophisticated residences, skyscrapers, and civic edifices.

Born in Hancock, Michigan, by the time of his high school graduation in 1900 Willard Close Northup (1882-1942) lived in Asheville, North Carolina, where his father owned a hardware store. To develop his architectural skills, young Northup attended the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry in Philadelphia, studied at the University of Pennsylvania, and was briefly employed by a Charleston, South Carolina, architecture firm. Returning to North Carolina, he gained experience in the offices of such established architects as Charles McMillen of Wilmington and Richard Sharp Smith and William H. Lord of Asheville. He moved briefly to Muskogee, Oklahoma, to work for the architectural firm of McKibbon and McKibbon, but soon returned to North Carolina, where in 1906 he opened his own practice in Winston (soon to become Winston-Salem). Willard Northup's first commissions were small residences, but he soon expanded his repertoire to include more ambitious Colonial Revival and Georgian Revival houses, plus other projects such as the Marshall Fields Factory Village in Fieldale, Virginia, and the O'Hanlon Building, North Carolina Baptist Hospital, Winston-Salem City Market, and Salem Town Hall and Fire Station in Winston-Salem.

In 1907, with his practice thriving, Northup hired a young draftsman, Winston-Salem native Leet Alexander O'Brien (1891-1963). O'Brien was a graduate of the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh and had worked in that city for the architectural firm of Ingham and Boyd for several years before returning to North Carolina.

Northup and O'Brien formed their partnership firm in 1915 or 1916 and established a strong reputation for their religious, commercial, and institutional work, with a specialty in consolidated schools during a period when state and local investment in public education was mounting. Both men served in World War I. O'Brien, who was exempted from the draft due to his poor eyesight, was stationed at the Navy Bureau of Yards and Docks in Washington, DC. Northup went abroad to oversee military camp construction for two years, achieving the rank of captain.

Meanwhile, Northup had begun his vital and lasting role in the promotion of the architectural profession in North Carolina. In 1913, he was one of five North Carolina architects (see Glenn Brown) instrumental in founding a state chapter of the American Institute of Architects (NCAIA), and he was equally important in the passage of legislation regulating architectural practice in 1915. Northup served the North Carolina Chapter of the AIA as education chairman in 1913, treasurer-secretary from 1913 to 1916, vice-president in 1916, and president in 1921. In 1932 he received one of the highest honors of the AIA--elevation to fellowship as FAIA. In 1919, Northup was appointed president of the North Carolina Board of Architecture, a position he held until 1931 and again from 1933 until his death in 1942.

Leet O'Brien also participated in professional organizations, becoming an AIA member in 1925, joining the North Carolina Society of Engineers, directing the Winston-Salem Engineers Club, and serving on the advisory committees of the North Carolina State Planning Board, the North Carolina Arts Society, and the North Carolina Engineering Foundation. He was elected treasurer-secretary of NCAIA in 1927, vice-president in 1932-1933, and president in 1934-1935. When planning began in the late 1940s for a new architecture school at North Carolina State College, O'Brien suggested that the NCAIA create a foundation to support the program. Northup and O'BrienpartnerLuther Lashmit, Charlotte architect Walter W. Hook, and Raleigh architect William H. Deitrick incorporated the North Carolina Architectural Foundation, which later became the North Carolina Design Foundation, in 1949.

Many talented architects began their careers working for Northup and O'Brien. The firm hired Durham native George Watts Carr, educated at Davidson College and the Eastman Business School in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1926 to supervise their projects in his thriving hometown. Carr established his own Durham practice in 1927, which continued until he retired in 1974.

A key figure in the Northup and O'Brien firm, and one of the state's outstanding architects of the mid-20th century, was Winston-Salem native Luther Lashmit. Although he did not become a partner until 1945, Lashmit was a vital part of the firm from 1927 onward and lead architect for some of its premier projects. Lashmit graduated from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, traveled in Europe, and taught at the Georgia Institute of Technology before returning to Winston-Salem to work with Northup and O'Brien. He took on the prestigious project of designing Graylyn, the opulent and up-to-date Norman Revival-style residence of R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company president Bowman Gray and his wife Nathalie Lyons Gray; the project began in 1927 and was not completed until 1932. Lashmit left Northup and O'Brien in 1933 to teach at Carnegie Institute until 1938, when he rejoined the firm and in 1939 designed another distinctive residential project, Merry Acres (R.J. Reynolds, Jr., House), the streamlined International style home for the son of the founder of the Reynolds Tobacco Company. In 1942, Luther Lashmit took another leave from the firm to work for the Federal Public Housing Authority, and upon his return home in 1945 became a partner in Northup and O'Brien. After O'Brien retired in 1953, Luther Lashmit formed a partnership with engineers Mack D. Brown and William W. Pollock, who had joined the firm in 1929 and 1936, respectively, and architect William Russell James, Jr., to reorganize the firm under the name Lashmit, James, Brown, and Pollock. After several additional partnership changes over the years, the successor firm became Calloway Johnson Moore and West in 1994 and now operates under the initials CJMW.

Northup and O'Brien's commissions encompassed hundreds of commercial, institutional, educational, ecclesiastical, and residential buildings throughout North Carolina in a full range of popular 20th architectural styles. An unusual quantity of their architectural drawings survives (see note below), including several in Winston-Salem repositories and those for some 300 projects at Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University Libraries, in Raleigh.

In his early work in Winston-Salem, Northup incorporated distinctive architectural features seen in older Salem buildings--particularly the arched entrance "bonnet" hood design at the venerable Home Moravian Church--into new edifices such as the Salem Town Hall (1912), the last municipal building erected before Salem's consolidation with Winston in 1913. Honoring Salem's Moravian heritage, he specified bonnet hoods over the corner entrances. When he drew plans for the Rondthaler Memorial Building (1913) to expand facilities at Home Moravian Church, he repeated many of the older building's features, including the round-arched entrance hood. Northup and O'Brien produced many renditions of the "Salem Revival" style, which became a localized version of the widely popular Colonial Revival style. The firm's many church designs included those for Moravian congregations, such as Calvary Moravian Church (1925) and Ardmore Moravian Church (1931) in Winston-Salem. By contrast, Fairview Moravian Church (1923), in Winston-Salem displays the more generally popular Neoclassical Revival style.

Northup and O'Brien's commercial building designs range from modest storefronts to skyscrapers. Winston-Salem examples include the Art Deco style Sosnick's Department Store (1929), and skyscrapers such as the 8-story Neoclassical Revival style O'Hanlon Building (1915) and the 6-story Pepper Building (1929), in variegated brown brick and sandstone veneer with Art Deco detailing. One of the firm's premier projects was the 15-story Durham Life Insurance Building in Raleigh, the city's tallest skyscraper upon its completion in 1942, with a stepped ziggurat form and elegant Art Deco detailing recalling Winston-Salem's iconic Reynolds Building by Shreve and Lamb.

Many local and state agencies commissioned Northup and O'Brien to design public buildings. The Renaissance Revival-style Winston-Salem City Hall, built in 1926 of red brick with a rusticated stone base and pilasters at the upper stories, was recognized by the North Carolina chapter of the AIA with an Honor Award in 1929. The Forsyth County Courthouse, erected in 1926 with limestone facing and enlarged in 1958, and the Justice Building in Raleigh (1938), constructed of Mount Airy Granite, show the firm's mastery of the austere, modernized classicism of the era.

The rapid expansion and greater complexity of medical facilities in the 20th century provided Northup and O'Brien with a steady source of commissions. The firm planned hospitals, nurses' housing, and other medical buildings, most of which have been razed or heavily altered. Among these projects were Forsyth County's second tuberculosis hospital (1930); that hospital's wing for black patients (1938); the state-of-the-art Art Deco-style Kate Bitting Reynolds Memorial Hospital (1938) built to serve Winston-Salem's African American community; the first building on the Bowman Gray School of Medicine campus (1940); and the major expansion of the adjacent North Carolina Baptist Hospital--all of which were executed in red brick with streamlined cast-stone details. The firm also planned the late 1940s renovations and new construction at present Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh (a psychiatric treatment facility) and the associated Dorothea Dix School of Nursing.

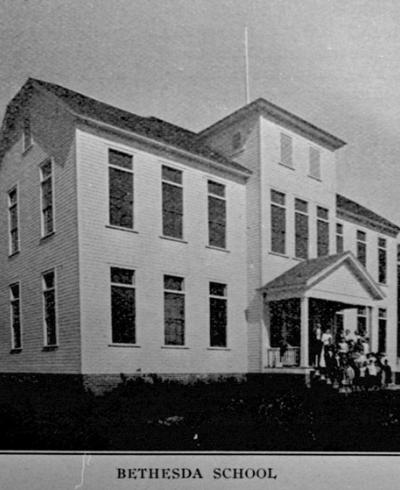

Northup and O'Brien also served the state's transformative investment in public school buildings in the early and middle years of the 20th century. By 1940, the firm had designed more than one hundred public consolidated schools statewide. Many have been replaced, but many still stand. Surviving examples in their home county include such Colonial and Neoclassical Revival-style buildings such as Clemmons School (1925), Old Town School (1926), and Griffith School and Gymnasium (1926), and one of Forsyth County's earliest modernist schools, Lewisville School (1948).

As the state's colleges expanded, Northup and O'Brien designed buildings and site plans for many old and new campuses. Their Winston-Salem commissions included projects at Salem Academy and College; Winston-Salem State University; the Methodist Children's Home; and Memorial Industrial School. Farther afield, the firm planned buildings at present Appalachian State University in Boone, Davidson College near Charlotte, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina State University in Raleigh, and North Carolina Wesleyan College in Rocky Mount.

By the time the firm's founders died or retired, Northup and O'Brien's oeuvre was among the most extensive, varied, and distinguished in the state. Not addressed in this summary is how these men interacted with the state and local leaders who developed North Carolina into the notably progressive state of the mid-20th century. Certain it is that Northup, O'Brien, and Luther Lashmit played a role in that transformation, and their legacy stands not only in the buildings of their home community but in public, private, and institutional buildings throughout much of the state.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.