Note: I've relied heavily on P. Preston Reynolds' excellent history of Watts Hospital - "Watts Hospital: 1895-1976. Keeping the Doors Open." in writing this entry. It's the best place-based book about a structure/set of structures in Durham - I highly recommend it for further reading if you are particularly interested in the hospital/hospital campus.

The original Watts Hospital - Durham's first hospital - had been established by George Watts on February 21, 1895 to provide hospital care to white men and women of Durham. The original hospital was a frame 'cottage' hospital located at the corner of Guess Road and West Main St.

Within 10 years, patient demand had outstripped the capacity of the old hospital. Watts made plans to expand the hospital on site, and engaged the firm which had designed the original hospital - Rand and Taylor of Boston, MA. Taylor, however, came to Watts with a proposal for an entirely new hospital - ambitious in scale and far from the "smoke, noise, and trains" in town. Taylor evidently placed multiple petri dishes around Durham, and chose the site that grew the fewest bugs - a 56 (or 43, or 60, depending on the source) acre tract at the northwest edge of town - outside of city limits, actually, in West Durham. The site was a "splendid grove of oak and hickory."

Ground was broken in May 1908, and the hospital was dedicated on December 2, 1909. Watts spent $217,000 on the site and construction.

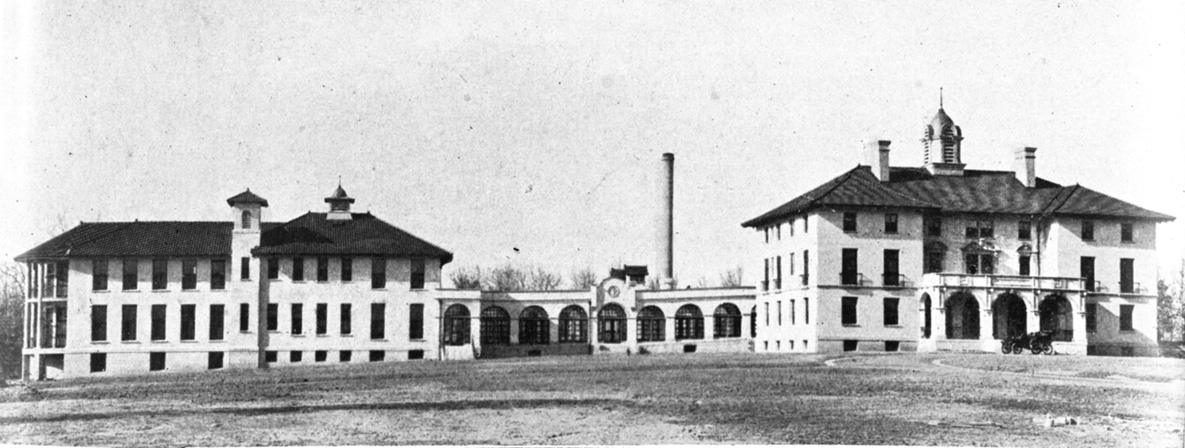

Under construction, looking northwest from Broad St., 1909.

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection - Chamber of Commerce Collection)

The initial complex consisted of 5 buildings: an administration building, operating building, power house, laundry, and one patient pavilion.

Per Reynolds:

".. all the buildings were constructed of fire-proof materials. The front lobby walls were paneled in quarter-sawn oak.... The new features in the administration building included a small isolation ward of two beds and a pathological and bacteriological laboratory, which the architects thought was the first of its kind 'outside of the large cities of the South'. Near the main kitchen was a separate diet kitchen for the nursing students and another eating area for the [B]lack employees. The second floor accommodated private patients and maternity patients who were separated from one another by stairs, a nurse's station, and an elevator. The third floor provided living quarters for the nurses. Not counting infants, this building could hold 45 patients."

"The patient pavilion was two stories high and housed 14 patients on each floor. A dining room for the convalescents, a ward kitchen, elevator, work rooms, solarium, and balcony completed the picture."

"The operating building had an ambulance entrance, rooms for major and minor surgery, and a separate area for the care of accident victims. Builders installed a skylight in the major operating room to provide adequate light. The x-ray room opened to the surgical suites. The walls and floor were of marble, tile, and terrazzo."

Watts Hospital from Broad Street

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection)

The Watts-Hill families completed at least three other structures in a similar style to Watts Hospital: the Hill House, the Temple Building, and the Beverly Apartments. The last of these structures was given to the Board of Trustees of Watts Hospital in 1911 as an additional source of income.

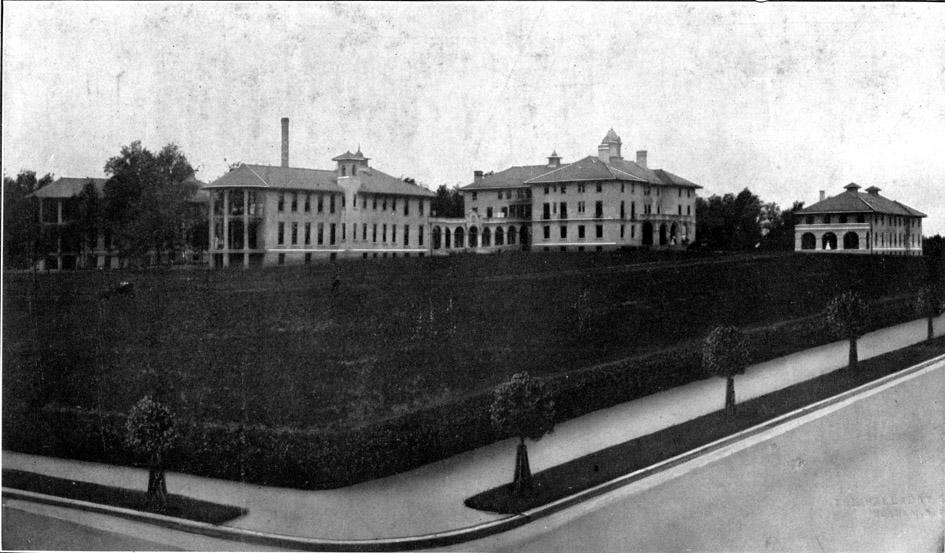

As at the original Watts Hospital, a nurse training program was an essential part of the facility. A nurses' home, named Wyche House after the 6th hospital administrator and nurse supervisor, Mary Wyche, started construction soon after completion of the original facility, and was completed in 1910 for $45,000. A separate patient pavilion for women was completed in 1911, also at a cost of $45,000.

Watts Hospital, 1915. From right to left: Wyche House, the administration building, the men's pavilion, and the women's pavilion.

(Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection)

George Watts provided additional funds to expand the laboratory and the x-ray department in 1919, as part of his ongoing quest to create facilities at Watts Hospital that were the equal of the northeastern hospitals that the wealthy of Durham had previously traveled to for treatment (particularly Johns Hopkins)

Watts Hospital, Main entry from Broad Street, ~1920.

(From "Watts Hospital: Keeping the Doors Open" by P. Preston Reynolds)

Looking northwest, 1920s.

(Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina)

He began to pull back from active involvement in the hospital as his own health began to fail that same year; John Sprunt Hill, his son-in-law, stepped in to many of Watts' responsibilities that same year. Watts' last living efforts for the hospital were attempts to work with President William Preston Few to establish a medical school for Trinity College, a school which would utilize Watts Hospital as its teaching facility. Watts' death in 1921 stymied this effort.

Watts provided shares in the British-American Tobacco Co. and $200,000 to the hospital in his will. He stipulated that the hospital should construct a new patient wing to honor his first wife, Laura Valinda Beall Watts.

John Sprunt Hill took the mantle of President of the Board of Trustees after Watts' death, and began to champion the cause of a medical school affiliated with Watts Hospital. He devised the "Durham Plan" to establish the North Carolina Medical School in Durham. The state legislature would issue $4 million in bonds, $4 million would be collected from private sources, and Watts Hospital would provide $1.5 million. However, Hill suddenly dropped the campaign - at about the same time that James B. Duke asked Hill to help him craft the charter to establish the Duke Endowment.

A third generation of Watts-Hill joined the stewardship of Watts Hospital in 1925 when George Watts Hill became chairman of the building committee. Soon after, the hospital board began the work to expand the hospital with the new patient pavillion; they hired Taylor (by then Taylor and Kendall) to design the patient pavilion provided for by George Watts' will. The Valinda Beall Watts Pavilion was completed in 1927; it served urology and pediatrics, and had 50 private rooms, along with a kitchen serving the private patients. A radiology suite was constructed in 1934.

Per the Durham Centennial Edition in 1953 "two additions" to Watts Hospital were built by contractor George W. Kane, but I'm not sure which two.

Aerial view of Watts Hospital looking northwest, including the newly completed Valinda Beall Watts pavilion, late 1920s.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

Valinda Beall Watts pavilion, 1930s

(Courtesy Durham County Library - North Carolina Collection)

West entrance to Watts Hospital, late 1920s.

(Courtesy Durham County Library - North Carolina Collection)

New competition was afoot for Watts Hospital; James B. Duke's endowment of Trinity College to become Duke University provided for the establishment of a medical school and hospital with the new university campus. Watts Hospital had no explicit role in the new medical school when Duke Hospital opened in July 1930. But the attraction of new medical professionals to Durham, particularly specialists, proved somewhat of a boon initially for Watts as the new staff often practiced at Watts as well. Soon, however, competition was acute, as Duke and Watts both opened outpatient clinics in 1931. Duke clearly did not mean to steer clear of the role of community hospital.

Interestingly, Durham had always provided minimal support for the hospital, which George Watts had stipulated should provide care to the community regardless of a patient's ability to pay. City and County donations to the hospital to offset charity care covered ~ 1/3 of the costs in the early 1930s. As the cost of medical care continued to grow, ironically, with the successful treatment of acute disease and rise in preventive care, hospitals nationwide, including Watts, would grapple with how to procure sufficient funding.

Watts Hospital was in somewhat of a unique position because of its First Family, the Watts-Hills, and their explicit involvement in the formation modern health insurance. I've written a bit about this on my post about the George Watts house (Harwood Hall), which would become the site of the Hospital Care Association building by the 1960s. This organization would later become Blue Cross-Blue Shield of North Carolina.

Watts would also play a role in training nurses during World War II - a significant mobilization of Federal funds into health care and medical training. In 1945, the Hill House - a dormitory and classroom building for the nursing school - was built to the west of the earlier Wyche House, funded primarily by Federal funds. The passage of the Hill-Burton Act in 1942 would provide for Federal funding to support construction of hospital facilities nationwide.

1938 view of West Club Blvd, with the hospital grounds to the left.

(Courtesy Duke Forest Collection)

1945 aerial, looking west-northwest, showing the new Hill House to the north of the original hospital wings.

(From "Watts Hospital: Keeping the Doors Open" by P. Preston Reynolds)

Old Administration Building, 1950s

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

In 1953, a George Watts Carr designed addition, which included a new emergency room entrance, main entrance, modern delivery/operating rooms, new xray, lab, and kitchen facilities, as well as 100 new beds was constructed west of the Valinda Beall Watts Pavilion. The addition cost $2,577,000 to build, and opened on December 20, 1953.

(Courtesy John Schelp)

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

Construction of new emergency entrance, 08.29.56

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

The increasing reliance on Federal and state funding to support capital and operating costs at Watts would also, eventually, lead to the ultimate demise of Watts hospital, as Federal legislation - including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the enactment of Medicare in 1965 - would demand that hospitals be racially integrated.

Like most institutions in Durham, the hospital system was racially segregated - Watts had, until the 1960s, always served only white patients. One of the more unique things about Durham has always been the strength of the African-American community during the segregation era; when Watts had originally proposed adding a wing to Watts Hospital to treat African-American patients in 1900, he was persuaded by the African-American community that this was not in their best interest. The better solution would be to construct a hospital where African-Americans could both be seen as patients and be medical providers. The result was the construction of the original Lincoln Hospital in 1901. Lincoln grew and prospered as an institution and moved to new, larger quarters on Fayetteville St. in 1925.

This led to interesting motivations in the move towards desegregation in the 1960s. By that time, despite large additions to both Lincoln and Watts Hospitals in the 1950, the two were providing hospital facilities to Durham that would be difficult to retrofit for evolving patient needs/desires.

As the larger of the two institutions, with greater room to expand, Watts was seen by the white community as the natural location for an expanded, consolidated hospital for Durham. A Hospital Study Committee also found that the patient census at Lincoln was low. Duke Hospital had always treated both whites and African-Americans, although it was internally segregated. But Duke had fully integrated its patient services in the 1950s.

Like many of the segregated institutions of the African-American community, Lincoln was no longer exclusively, or even widely patronized by the 1960s. The migration of the African-American consumer to new choices meant the demise of many retail establishments, as well as institutions such as Lincoln. Like much of Hayti, though, community leaders attached an understandably fierce pride to Lincoln, and the symbolism attached to its proposed closing was powerful. Fear regarding the adherence of Watts to a true integration of patient services, with equal care provided to African-Americans and whites was quite real.

In October 1964, the Watts Hospital Board of Trustees voted 7-4 to integrate Watts Hospital.

A $15 million bond was proposed to enact a plan proposed by the Health Planning Council, a group comprised of leaders from both Watts and Lincoln Hospitals as well as others. The plan would involve the expansion of a now-integrated Watts Hospital to become the primary hospital for the community. Lincoln would have reduced services, but continue to exist with some upgraded facilities. From the start, the bond issue struggled. Durham has had multiple instances, to this day, where the African-American community and the conservative white community find their interests aligned. This was one of those instances - the conservative white community (represented by the "White Citizens Council") objected to a single primary hospital for both the white and African-American community, as they favored segregation. The African-American community (represented by the then-"Durham Committee on Negro Affairs") also objected - because of the reduced role for Lincoln.

The bond issue was soundly defeated in November 1966.

A multi-racial Hospital Study Committee was set up, which recommended the construction of a new hospital, and the conversion of Lincoln and Watts into extended-care facilities. This initially also met with opposition, but eventually all parties agreed to the need for a new facility, after assurances that it would provide equal integrated facilities for African-American patients and medical staff. The $20 million bond measure passed by a 2-1 margin on November 4, 1968. This would lead to the construction of Durham County General Hospital on the former County Home site on N. Roxboro Road. Seemingly, the only way to move past the old divide between Watts and Lincoln was to start anew. This facility would be renamed Durham Regional Hospital in the 1990s.

(Reynolds does a wonderful job breaking down the political motivations and perverse incentives at play during the push to both grow Durham's hospital facilities and integrate them at the same time. )

Main entrance, 07.17.70

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

The new hospital was completed and ready for patients in 1976. On October 10th of that year, all patients were transferred from Watts to Durham County General. (Patients at Lincoln had previously been transferred to Watts in September of that year.)

Watts was never transformed into a health facility - administration offices and the nursing school remained on site until the early 1980s. It presented an ideal venue for another institution, however.

The idea of a 'magnet-school-for-North-Carolina' originated with Governor Terry Sanford, and was continued by Jim Hunt. In 1977, the goal of establishing a public, residential high school that would attract talented students from throughout the state was brought before the General Assembly. In June 1978, the GA approved $150,000 in funds to begin a search process for a suitable site and establish the school. In November 1978, Durham was named the host city for the school, which would be known as the North Carolina School of Science and Math.

In September 1980, the school opened its doors with 150 high school students -the first state residential high school of its kind. It currently serves 650 high school Juniors and Seniors from throughout North Carolina with a specialized curriculum in math and science.

Former Watts Hospital Administration Building, 09.12.09

Former Men's Patient Pavilion, 09.12.09

Former Women's Patient Pavilion (left) and X-ray pavilion (right), 09.12.09

Former Wyche House/Nursing Students' Home, 09.12.09

Former Valinda Beall Watts Pavilion, 09.12.09

1953 "Brick Addition" to Watts Hospital, 09.12.09

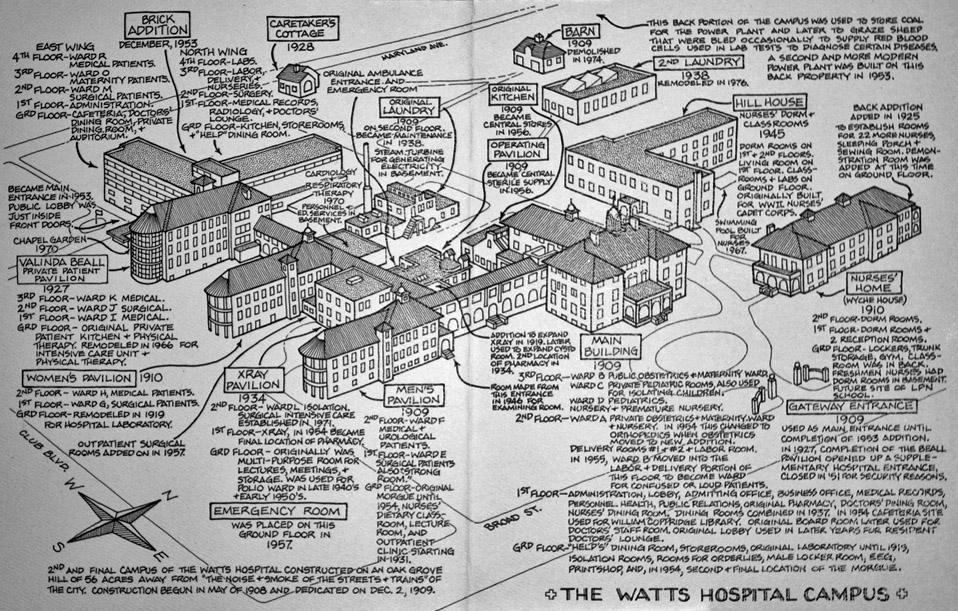

Below, a drawing that NCSSM handed out during the Watts-Hillandale tour showing the buildings on the campus, dates, and historical uses. The drawing is also in Preston Reynolds' book.

Comments

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Fri, 10/30/2009 - 9:00am

Funny how memory works. Just looking at the pictures, I can almost smell that particular hospital odor (sanitizers I suppose) and remember the sounds of the emergency room from when I was there as a kid.

When you say it was the first residentual state high school of its kind, do you mean for math and science? Because North Carolina Scool of the Arts had both junior high and high school residential arts students in the 1970s.

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Fri, 10/30/2009 - 12:22pm

The caretaker cottage has had a life of its own, having been moved twice during the existence of NCSSM. First to between the "1954 building", then later when the new Frederick building was built to its current location between Wyche House/Royall Center and Broad Street.

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Fri, 10/30/2009 - 1:51pm

thanks for this Gary. Your highlights are an incredible service

Submitted by Michael Bacon (not verified) on Fri, 10/30/2009 - 3:12pm

I have the distinction of being one of a handful of people to have both a birth certificate and a diploma from this location. Obviously, I remember considerably less about obtaining the first, but in 1976, the maternity ward was on the third floor of what at least now is known as the Brian (Bryan?) building, about where I had my Research in Biology class my senior year.

A few bits of history to note since it's been opened as the school. Wyche, now the Royall Center, was a condemned building even through 1994 when I was there. It had served as a dorm in the early years of the school, before asbestos was discovered during the asbestos scare of the late 1980's, and the building was vacated in a matter of hours. The only used part of the building was a holography lab in the basement, but it had a back porch of sorts that was one of the two designated smoking area for campus. In the early 90's, this meant that the "Wycher" crowd was a general cast of smokers, long hairs, flannel wearers, and other excellent disreputable types. (I wasn't a Wycher, but had lots of friends who were.)

I believe it was 1990 that a new dormatory was built on the north side of campus, north of Hill Hall, the 1950's-era nurses dormatory to the west of Wyche. It was soon named the James B. Hunt dormatory, after all Hunt did to start the school, but in the typical contrary nature of the students, everyone refused for years to actually call it that, and so it was unofficially still "New Dorm" up until I left.

The Charles Eilber physical education center ("the PEC") in the northwestern section of the campus was built largely upon the efforts of and named after one of the first chancellors. Similarly, the John Frederick Education and Technology Center on the west end of Brian became the focus of "Director Frederick's" term towards the end of his career, where he pursued the money and the plans to build it. (It was about the same time that the new entry lobby on the front of Brian was built). Both of these were part of a general theme -- directors of the school who were reviled by students and faced open revolt by faculty during their duration, and whose terms improved immensely when they quit messing with the running of the school and went off to build a building. I rolled my eyes at the opening of the ETC when they announced it would be named after Frederick (I was sitting next to my old principal, so couldn't say too much), but current faculty said it was entirely appropriate, as he was the one who did everything to get it built, and that this was a godsend because it kept him from causing trouble elsewhere. From everything I've heard about current President Boarman (he changed the name of the position for whatever reason), and his predilection for insane security measures and faculty harassment, I think most of the school can't wait until he decides to start working on a building. (The N&O, having done with Mike Easley for the moment, appears to be turning their attention to Boarman, which I think I need to start making popcorn for.)

I can't quite remember where it used to be, but the "cabin" at the northeast corner is a historic building, but not in its historic location. Either just before I arrived there, or between my years there, it was moved to make room for some new project.

Submitted by Michael Bacon (not verified) on Fri, 10/30/2009 - 3:12pm

The original powerhouse was still standing when I was there, to the north of the Reynolds pavilion, or the southern, patient wing of the original facility (which I actually had no idea was part of the original complex -- I thought it was an addition). It apparently suffered an explosion and collapse at some point, because those who broke in and looked around reported that the enormous flywheel and other old steam equipment was still in there, thrown off its moorings. The building has since been removed -- I do hope some steampunk got a hold of the old equipment.

The odd "sundial" sculpture to the north of Brian, which in my opinion is pretty aesthetically crappy, is also apparently assembled incorrectly. The steel-reinforced concrete was built with a bias to resist warp in one direction, but was assembled upside-down. One can hope this might mean it will fall over sooner.

During my senior year, some made-for-tv-movie signed some agreement to use the campus for filming, primarily the old administrative wing (now just called "Watts") and put an enormous sign over the front gates that said, "State Colony for the Eplieptic and Feebleminded." We of course all went out and got our pictures taken by the sign.

And finally, the bicycle shelter on the west side of Hill Hall was a student Special Projects Week endeavor of some friends of mine. I was writing a computerized population simulator at the time, and took breaks to go pound nails with them.

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Fri, 10/30/2009 - 6:24pm

ahh, man, thanks for posting this. it's amazing, some of those 1920s and 1930s pics look exactly the same as ones i took there, just the trees are a little bigger. the history of the hospital is fascinating. (i graduated from ncssm in '99.)

Submitted by Cathy (not verified) on Fri, 10/30/2009 - 7:58pm

The movie Michael refers to was "Against her Will; the Carrie Buck Story", a Lifetime movie about the seminal forced-sterilization case.

And I think it is Bryan, not Brian.

Submitted by Michael Bacon (not verified) on Fri, 10/30/2009 - 10:19pm

Thanks, Cathy. I thought it was Bryan, then I couldn't convince myself that it looked right.

Submitted by John Schelp (not verified) on Sat, 10/31/2009 - 12:29pm

When NCSSM was just getting off the ground, the new administration noticed the sinks in some of the buildings were often stopped up -- and ordered new drainage pipes. The clogged pipes were removed and piled up in the woods behind the old hospital.

A long-time custodian asked school administrators if he could have the old pipes and they said yes. The custodian then made several trips with his pick-up, carting off all the old pipes.

The next day, the custodian called the folks at Science & Math to let them know he was retiring.

After years of medical waste going down the drain, the old hospital pipes were filled with silver.

(Story from long-time NCSSM teacher, Joe Liles.)

Submitted by Toby (not verified) on Mon, 11/2/2009 - 4:10am

@Michael - NCSSM has submitted plans to construct some more buildings in the central part of the campus. One result will apparently be the removal of the bike shed. I took a walk over there this evening, and for the life of me I can't really understand how that bike shed could be very useful. The 80-100 bikes stored in it are in such close proximity that it would be difficult to get one out without having to move 10-15 others. The original wooden framed structure is now ringed with a chain-link fence, making access that much more difficult.

Hopefully, the final plans will include a substantial amount of up-to-date bicycle parking distributed around the whole campus.

Submitted by John Schelp (not verified) on Mon, 11/2/2009 - 3:45pm

Fresh from completing his hike of the Appalachian Trail, retired NCSSM teacher Joe Liles sent me a note to say the story of the silver-clogged pipes happened back in the 1950s.

According to Joe, the clogged sinks were in the X-ray department -- when it was on the upper floors of the Emergency Room addition, near the Surgical Suite (ie. current location of the NCSSM Art Studio). The pipes were cast iron and attracted the silver that was dissolved in the fixer used in processing the X-rays. The cast iron pipes were replaced with good old PVC.

Folks at Watts Hospital thought the custodian who asked for the pipes back in the woods was crazy, but he got the last laugh. (Thanks, Joe!)

Submitted by cg (not verified) on Tue, 11/3/2009 - 2:42pm

Born there, but have an aversion to science and math, so I have the irony but not the diploma.

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Sun, 11/22/2009 - 9:51pm

Wow, this was a great read. Thank you! For those who'd like to see more old images of Watts Hospital, see:

http://www.kspot.org/watts/

--NCSSM, c/o 1992

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on Mon, 4/19/2010 - 2:19am

To whom that may know, what was the name of the first African American child born at Watts during segregation? Please reply to kiddee723@yahoo.com. thank you D Parker

Submitted by M.C. Sims (not verified) on Mon, 10/31/2011 - 4:50pm

Wow--so glad I found this website! I was born here at Watts, but moved to Georgia in mid fifties.

Submitted by F. K. (not verified) on Wed, 9/12/2012 - 6:23pm

just before its conversion to NCSSM, they put on a Halloween "haunted hospital" show for local school children. I was at EK Powe at the time, and we walked up Ninth street. Talk about creepy!

Submitted by Palmer Clifton… (not verified) on Mon, 4/29/2013 - 7:06pm

Great info! I'm class of '87, and I *will* correct you on the construction of Hunt, though. It was built during the '85-'86 school year, and still wasn't ready for the '86-'87 class by August. A whole bunch of the boys were housed in the Carolina Duke Motor Lodge down on Guess Road for a couple of months that fall. They had to walk up to campus, but they also had a swimming pool! I lived on 1st Wyche, on the west side, and the construction of Hunt aka New Dorm interrupted my (frequent) daytime naps, though it was interesting to watch it go up!

(And I think it was more state politics than student recalcitrance that prevented "New Dorm" from being named Hunt upon completion. We all knew at the time that the intended name was Hunt, and couldn't believe they wouldn't make it official. I'm surprised while reading this just how long it took!)

Submitted by Braxton Baird (not verified) on Mon, 10/7/2013 - 9:36pm

Learning about the history of this campus is very interesting and hearing about the past students that used to live here. I am currently a junior at Science and Math and enjoy learning about its history and the stories behind it.

Submitted by Braxton baird … (not verified) on Fri, 10/11/2013 - 8:48pm

Attention all former students of NCSSM, we are CURRENT students conducting a mini-term much like past ones on the haunting of the School. So far we're investigating Ground Reynolds morgue and lab, as well as the ever so famous Hill tunnel. We would like to know any of the stories you have heard regarding paranormal activity, as well as any other possibly haunted areas.

Contact Information

Braxton Baird- baird15b@ncssm.edu

NaBriya Ware- ware15n@ncssm.edu

Submitted by Catherine C. (not verified) on Sat, 6/21/2014 - 6:39pm

The dorm was officially named Hunt at the beginning of the 1990-91 school year, which partially explains why the naming transition among students was complete by around 1994. Those who started at the school in 1989 (class of 1991) learned to call it New Dorm, and the ND designation for the rooms themselves lasted until the end of the 1990-91 school year. The H designation popped up during 1991-92, so the incoming class of 1993 called it Hunt from the very beginning -- but the outgoing class of 1992 had been taught to call it New Dorm and tended to move back and forth depending on mood and audience.

-- NCSSM c/o '92, who still insists it's called New Dorm

Submitted by Fred L. Haney, Jr. (not verified) on Sun, 6/22/2014 - 5:24pm

I was born at Watts Hospital on October 1, 1936..........

Fred

Submitted by Joseph Sparks on Thu, 10/30/2014 - 4:37pm

First surgery, 1969 at 16 years old was my appendectomy done here at Watts Hospital. Wow a lot has changed in medicine since then. Thankfully!

Submitted by Joseph Sparks on Thu, 10/30/2014 - 4:46pm

Also being young in those years of the 60s and living a couple of blocks away, my friends and I roamed all over the area and Durham at large. At Watts Hospital we made friends with the boiler keeper and would visit him at night. I even climbed the boiler chimney, which was pretty tall, on a dare. I was never afraid of heights obviously. Great memories. Especially when the hospital installed a covered swimming pool for the nursing students to use out back near the boiler room. Young boys, watching all those pretty nurses come and go to the pool was a lot of fun to say the least. Good times, good times! But...we were always gentelmen first and foremost!

Submitted by Joseph Sparks on Thu, 10/30/2014 - 4:48pm

In reply to Also being young in those by Joseph Sparks

Wish there was a way to edit my posts to correct spelling. That'll teach me to preview first!

Submitted by Joseph Sparks on Thu, 10/30/2014 - 4:46pm

Also being young in those years of the 60s and living a couple of blocks away, my friends and I roamed all over the area and Durham at large. At Watts Hospital we made friends with the boiler keeper and would visit him at night. I even climbed the boiler chimney, which was pretty tall, on a dare. I was never afraid of heights obviously. Great memories. Especially when the hospital installed a covered swimming pool for the nursing students to use out back near the boiler room. Young boys, watching all those pretty nurses come and go to the pool was a lot of fun to say the least. Good times, good times! But...we were always gentlemen first and foremost!

Submitted by Charlie Gibbs on Wed, 5/10/2017 - 9:38pm

Response to M. Bacon 2009 comments;

John Schelp (to add to his history details)

M. Bacon: The initial campus renovations were made to the "' '54 Building" (some references as the "Brick Addition" by some accounts...). The architectural firm Carr, Harrison, Pruden & DePasquale Architects was selected by DCHC for this first renovation project to provide dorm space, kitchen/dining renovations, various classrooms, was, as part of the project team, my first exposure to perceived precociousness of a talented, fortunate group of advanced high school students. As Dr Eilber (Chuck) said in a planning meeting, they ARE intelligent but they ARE young and need discipline, guidance. He realized, and was committed to, that Administration was entrusted with not only reaching their education potentials but also their safety and well-being. Parents were/are depending on that. Just a comment on my perception of comments alluding to possible disregard of adminstrative rules. (I realize it WAS a while back so I might be misunderstanding point of comments)

Regarding the establishment and development of the new NCSSM campus facilities, I also want to provide some interesting details of the near-fate, vs. "birth" of the Watts Hospital Campus to the now NCSSM, for first-hand documentation for interest and historic record.

Gov. Sanford's , Gov. Hunt's and others decision to establish a residential H.S. for advanced studies set off an intense statewide "competition" to have it locate in their city - Greensboro, Charlotte, Asheville, etc. and eventually a Durham proposal.

Durham came very close to not only losing the historic hospital structures but also a rare opportunity for a legitimate, attractive proposal to locate the prestigious school here, in Durham.

How close did we get to losing it ? I was in process of assembling bid packages for mailing to contractors after they'd paid their bid-bonds, etc.

All structures were to be demolished except the

'54 Addition. (again, another unwise administrative move by Durham decision-makers... familiar, huh ?)

Robert W. (Judge) Carr, senior partner in the architectural firm I worked in, Carr, Harrison, Pruden & DePasquale (Mr Carr's father was founder of the firm - George Watts Carr, Architects) had, in the meanwhile, during the demolition plans process, been assembling a group of local business leaders and conversations with close friend and NC Senator, Kenneth Royal with a proposal to convert the Watts Hosp. campus for submittal to the State as site for the school locating in Durham.

Mr. Carr had even drawn a proposed preliminary site development plan - all pro-bono.

The proposal continued to be presented in the State selection process.

Just before the bid-packages went out I was told to hold on the mailing.

The State site-selection committee had strong interest in the Durham location for the new residential high school at the former Watts Hosp. campus. And after reviews of all proposed sites, selected the Durham proposal.

The '54 Addition renovations for dorm, classrooms, etc. was initiated to meet a proposed opening date for the school. Mr. Carr and Edgar Carr, his son, architect and partner in the firm, were designers of the renovations and new campus buildings.

Campus development continued at steady pace to meet growth projections with a sequence of facility renovations of existing buildings and several new campus structures.

2. A first phase (my favorite part of the NCSSM project - surveying existing historic structures and converting to "modern" re-use) of campus expansion included renovating the original 1908 Hospital (to Administrative/Computer Classroom (VAX) / classrooms; Music Classrm/Performance Studio and original O.R. Suite (to Art Department studios). Addition of two required exterior emergency exit stairs on north and south sides of 1908 structure. Renovatios to connecting, paned-glass corridors from these back to the '54 Addn.

3. New 300-bed dormitory (boys and girls - seperate quarters of course) on north side of original hosp. bldgs., and utilities infrastructure and driveways configuration including reproduction of curved stucco drive entrance on Broad St.

The conical shaped Spanish tiles dorm roofs corresponded, blended with the curved roofs of the original patient pavillions on Club Blvd. elevations.

4. New Gymnasium-Multi-purpose building on north side, near Maryland Ave.

5. New Maintenance Facility building near the Gymnasium building.

This structure necessitated moving the original caretakers cottage. It was renovated and relocated on-site to serve as temporary living quarters for visiting teachers and dignitaries.

6. The large boilers in the original boiler plant bldg. for heating the hospital were replaced with new modern steam units, new steam lines, etc. and building renovated. The old hospital "medical incinerator/crematory" for disposal of "human parts", etc. from surgeries, etc., located on south side of boiler plant, was demolished.

Miscellaneous on-going upgrades to facilities and grounds occurred as funding became available.

A debt of gratitude to Robert W. Carr and others for their efforts.

In later years other architectural firms became involved for renovations of former patient pavilions

to dormitories, and later, main-entrance renovstion in '54 Addition building.

Submitted by:

Charles A. Gibbs

Architectural Draftsman - Carr, Harrison, Pruden & DePasquale, Architects

Submitted by Charlie Gibbs on Thu, 5/11/2017 - 3:33pm

In reply to Response to M. Bacon 2009 by Charlie Gibbs

NCSSM - Near-loss of Watts Hosp. campus vs. initial campus development sequence:

My previous posting (Response to M. Bacon....) is intended to describe events leading to eventual selection of

Watts Hosp. conversion to NCSSM campus - "first" advanced

curriculum residential high school for state of NC

By: c. gibbs

Submitted by John Schelp on Fri, 5/19/2017 - 12:22pm

When Erwin Cotton Mills on Ninth Street had a shift change, they'd momentarily stop the looms. This created an interesting problem for the new school at the end of Ninth Street. Stopping the looms resulted in a brief disturbance in the power supply, causing all the new computer/VAX machines to crash. So every afternoon, NCSSM took twenty minutes to re-boot their computers.

Another connection: cotton mills all over Durham (and beyond) used pattern cards in their looms. The holes in these cards determined the pattern, for instance, of the stripes in your shirts/blouses. These pattern cards were a precursor to IBM's punch cards -- used right down the road in Research Triangle Park.

Love these connections.

(Source for stopped looms/crashed computers: annual EK Powe reunion, first Sunday of May.)

Submitted by DHamm on Mon, 2/5/2018 - 3:19pm

Does anyone have any knowledge of adoptions taking place at Watts Hospital, around the time frame 1951? When my husband was 9 months of age, his adoptive parents came from Faison, NC to Watts Hospital, to pick him up. Whether all the adoption processes were done at another facility and this was just the pick up point, I am uncertain because all the parties who might have knowledge have passed away. In researching the history of Watts, there is never any mention of adoption services being conducted there. Our children are trying to locate the biological parents of their father, and this is the one piece of information we have.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.