Queer History of Durham Zine (Color)

Queer History of Durham Zine (Black and White)

Queer History of Durham Game

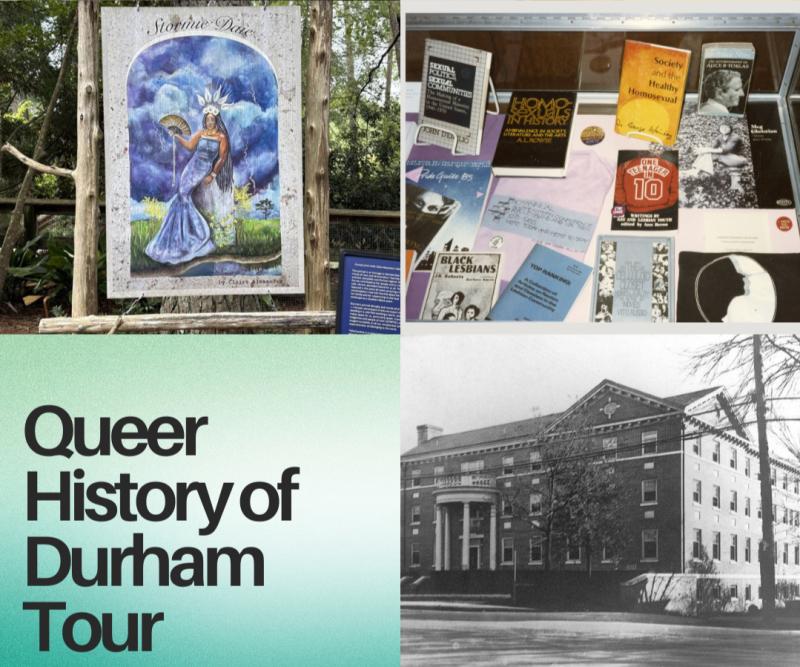

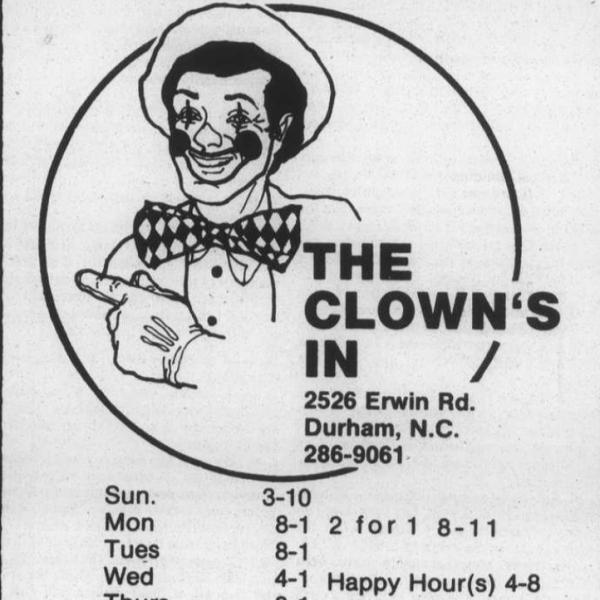

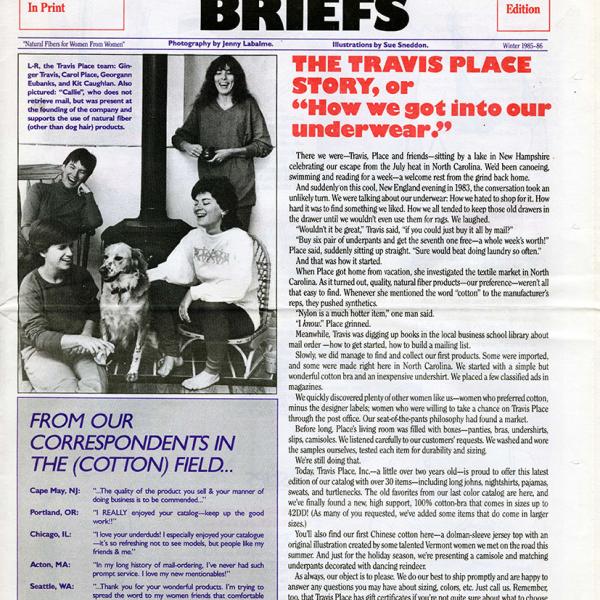

This tour grew out of a project from the Queer Public History class at North Carolina State University, taught by Dr. Megan Cherry. My cohort, Karina Burbank, and I (Julia Lasure, Membership and Programs Coordinator at Preservation Durham), both had specific ties to Durham and felt it was important to highlight the queer spaces found here. Durham was a hub in North Carolina for LGBTQ+ life and activism in the twentieth century and continues to be in the twenty-first century. As part of the Triangle, many queer people were drawn to Durham because of the local universities, finding community among the other queer people they met. Community was also created through popularly utilized queer spaces like bars. This tour includes a mix of social and community organizing spaces, demonstrating the variation of queer life in Durham in the mid to late twentieth century.

Preservation Durham had already received requests for a Queer History of Durham tour. This request, compounded with the understanding that sites associated with the LGBTQ+ communities are more likely to be demolished due to urban renewal and gentrification, inspired the creation of this program. Many of the sites on this tour are no longer here, which emphasizes the risks that historic buildings associated with the LGBTQ+ community face. Many of the sites were considered “deviant” or morally inappropriate by the city planners, or they were just so underground as to go unrecognized. Our goal with this tour is to teach, but also to advocate for the preservation of the extant sites we see throughout this tour.

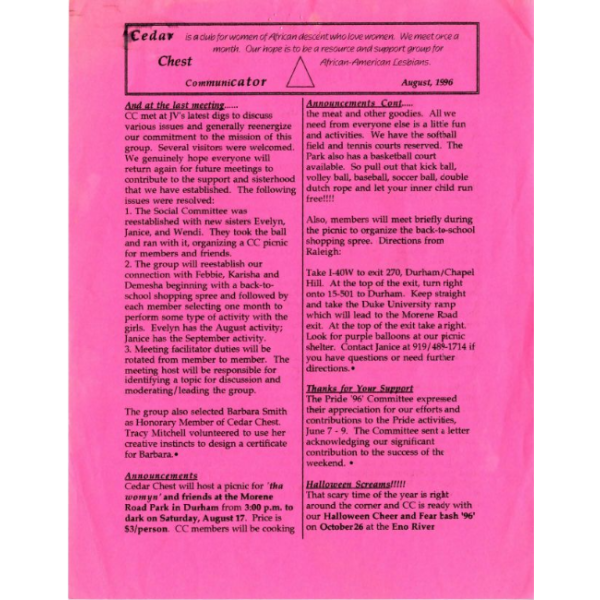

We want to note that many sites associated with women and people of color, and especially the intersection of the two, are located outside the downtown area. Queer women and people of color would meet outside of downtown areas for many reasons, including the need for more privacy, exclusion from white male-dominated spaces, or because of pay gaps that prevented these individuals from accessing the same opportunities as those commonly utilized by gay, white men. In some cases, like Cedar Chest, an organization for Black lesbians, groups met in private homes, rotating between members' houses.

Durham’s queer community is integral to the area’s history, making a mark through activism, cultural contributions, and the sheer existence in a southern state that has historically been slow to adopt equitable legislation and has continued to push anti-LGBTQ+ legislation throughout the twenty-first century. If you’ve been watching the news, you may have seen that notable sites associated with queer history, like Durham’s Pauli Murray Center, are being robbed of their queer and trans associations and are facing budget cuts due to grant eliminations. In this climate, it is as important as ever to highlight and educate the histories of the LGBTQ+ community.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.