Article from the Durham Morning Herald August 3, 1976

He Used His Ambition To Get a 200-Acre Chunk of Durham by George Lougee

From an interview with Claude Vickers

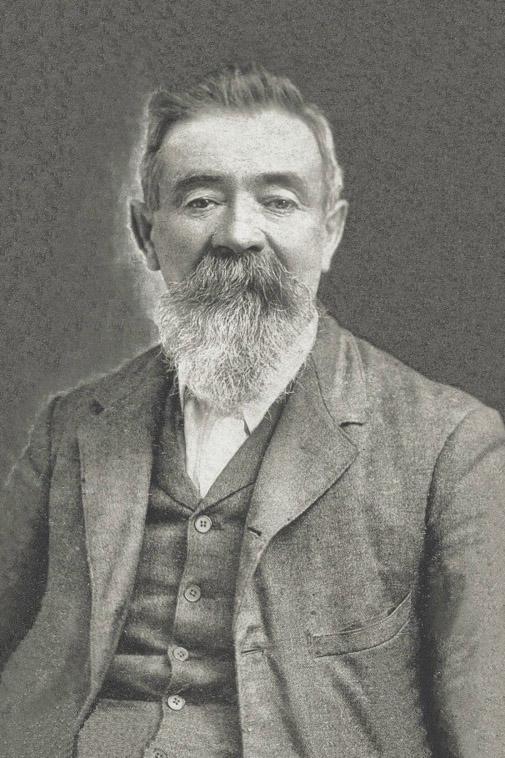

William Gaston Vickers was a man of ambition and personality.

He was born in 1838 in Orange County. As a boy her worked from sunup to sundown on a farm, his mother received $15 a year for his labor.

But at night, Gaston Vickers – they didn’t call him William – studied by firelight. In fact, he memorized the old Blue Back Speller and read everything he could lay his hands on.

By the time Gaston Vickers died in 1924, he had become a school teacher, Durham’s first superintendent of schools, a state legislator and a lay preacher. And Gaston Vickers – the boy who once worked for $15 a year – bought 200 acres of Durham for $1,500, and that land became the home for millionaires.

Gaston Vickers was first married to Nancy Emily Chisenhall and they had 12 children. He was next married to Genora Ann Wood and they had nine children.

Claude Travillian Vickers, 87, of Chapel Hill Road is Gaston Vickers only surviving child.

Claude Vickers remembers when his father was serving in the General Assembly.

“My brother Robert would take my father to Raleigh by buggy, leaving Durham early Monday morning,” Claude Vickers recalled. “My mother had to button up father’s white shirt in the back. He never wore a tie in his life, his beard covered the front of his shirt. He also wore a black clawhammer coat and striped trousers.”

He continued, “My daddy would sleep in his clothes all week. Robert would go back for him early Saturday morning and bring him back. Daddy always toted candy in his coat. When the candy gave out he would eat sugar. He never had diabetes in his life.”

Claude Vickers said his father was Speaker of the House and was credited with passing the 6 per cent interest law, and helped to pass a law providing that people who used barbed wire for fences had to put a six-inch-wide board on top of the fences to protect cattle and horses from getting cut up and blinded when they ran into the fence.

Gaston Vickers was a deacon at Second Baptist Church, which later became Temple Baptist Church on W. Chapel Hill Street. He donated land for the new church and took the pulpit as a lay preacher when the minister was absent.

Laughing, Claude Vickers said his father was “stingy with a nickel, dime and quarter, but was generous with his dollars, thousands of dollars.”

He recalled the time some Baptists came by the Vickers home, saying they needed money for their church. “Daddy, who was really a hardside Baptist, told me to write them a check for $1,500. I handled his business in his later years.

“He didn’t believe in fatalism – one man born to go to heaven and another one born to go to hell. He didn’t believe that. He said every man has a right to repent.”

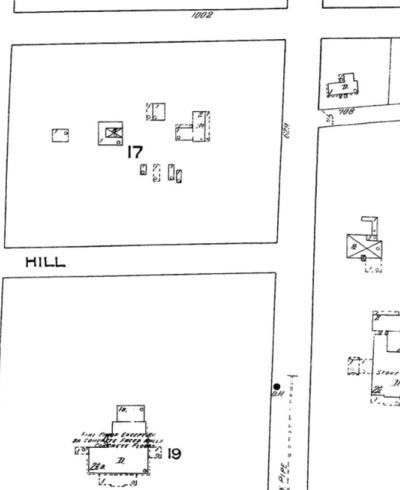

The 200-acre section of Durham Gaston Vickers owned included the Forest Hills shopping center and the tract between Duke and Kent streets up to Chapel Hill Street.

He gave the city right-of-way for 16 streets in the area and named Vickers Avenue for his family and four other streets for his children.

He built 100 houses in the area and kept them until his death in 1924.

Claude Vickers recalls how his father purchased the land:

“Well, my father was quite a fellow. He bought the land for $1,500 from his cousin, Atlas Rigsbee, and gave him a note for it. Atlas told him that the tract wasn’t worth that much because it was sorry land, mostly gullies. He said, “Gaston, if you hadn’t taught us all how to read and write, I’d never have sold it to you. You’ve been a smart man, but I’ll have that land back in 12 months.

“Atlas knew my father had 21 children and it cost money to raise them. But I heard my father say one time that if the women hadn’t given out he would have had more children.”

Claude Vickers said his father was sitting in the yard one day, wondering how he’d ever pay this $1,500 for the land, when up drove a handsome carriage pulled by two big, bob-tailed black horses. There was a driver and a passenger, George Watts.

“Mr. Watts said to my father, “Mr. Vickers, I’m moving from Baltimore to Durham to make my fortune. I have bought an interest in Duke’s Factory. You have a lot a Lee Street (Duke Street) and Morehead Avenue. I want to buy that whole block. Will you sell it to me?”

“Daddy said the land wasn’t for sale. ‘Won’t you make me some price.’ Mr. Watts asked. My daddy answered yes, thinking he would make it so high Watts couldn’t buy it. He said, “Mr. Watts, I’ll take $1,500 for that block.” Mr. Watts smiled and nodded. He said, “Thank you, Mr. Vickers. Your check will be ready for you at 9 o’clock tomorrow morning.”

“The next morning my daddy picked up the check and wrote a deed by hand. He cashed the check and went over to Atlas Rigsbee’s home. Atlas laughed when he saw daddy coming. He said, “Gaston, are you getting ready to ask me to take that land back?”

“My daddy calmly shook his head. ‘I came to pay you for it and take up the note’ he said almost casually.

“Atlas was astonished. When daddy told him how he had realized the whole amount in just one land deal and so quickly, Atlas just couldn’t get over it,” Vickers laughed.

“And that’s how it happened. ‘Yes, sir, that 200 acres of land would easily be worth $100 million today,” he said.

Claude Vickers said that his father offered to give the city a beautifully wooded tract of land from Cobb Street to Wells Street, as the site of a park to be named Vickers Park, but the city declined the offer.

“Our home was in the middle of the block of Vickers Avenue across from the Allied Arts Building. The city limits ran through the middle of our house and the children who went to the city schools had to sleep on the east side of the house, which was inside the city. That was when daddy was married for the first time,” Claude Vickers said.

“He had two brothers, Tom and Marion, both of whom were killed in the Civil War. Daddy’s mother is buried in the Rigsbee burial ground near the east gate of the Duke football stadium.”

Shaking his head, Vickers said, “Durham has torn down too many nice old homes. Mr. Watts sold half of his land to Mayor Morehead for the site of a fine home. Mr. Watts built a mansion on his part of the tract. Of course, the Watts mansion was leveled and the ground was used as the site for the Blue Cross building. I’m glad that his son-in-law, John Sprunt Hill, who lived in a mansion just south of the Watts home, left his place to the women of Durham.”

The Hill home is now used by the Anne Watts Hill Foundation and the Junior League of Durham.

Submitted by Dick Pickett (not verified) on Sat, 10/11/2014 - 1:40am

Was born in what was Orange but now is Durham County, September 16. 1838. Educated in the common schools of the neighborhood, having been deprived of a father's care, and had to support his mother. He went to farming; quit that, and was engaged in teaching school for thirty years. Was elected Superintendent of Public Instruction of Durham County for five years, and was a member of the Board of Education. Was married to Miss Emily Chisenhall, of Durham County, in 1859, and 1 December she died. 26 August 1883 he was married to Miss Genora A. Wood, of the same county, and is the father of nineteen children.

Mr. Vickers was a Democrat up to 1893, when he changed for the Third party, and in 1894 was elected to the House of Representatives by a large majority.

--GENERAL ASSEMBLY Of NORTH CAROLINA, SESSION OF 1895.

Durham Newspaper Article 4/26/1900

What ought to be done

Yes, William Gaston Vickers does say that he voted against the Confederate monument resolution and is proud of it. The following is clipped from the Chapel Hill News:

Maj. Guthrie said in his speech Saturday that Gaston Vickers, the Rep-Pop candidate in this district for senator, voted against the resolution appropriating money to finish the monument to Confederate soldiers. He said the man who would not do that much for the honored Confederate dead ought to be sent to the Philippine Islands, shot in the head by a Negro and buried in a swamp where the foot of the white man would never tread.

(Gaston's brothers, Washington & Thomas, died in the service of the Confederacy.)

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.