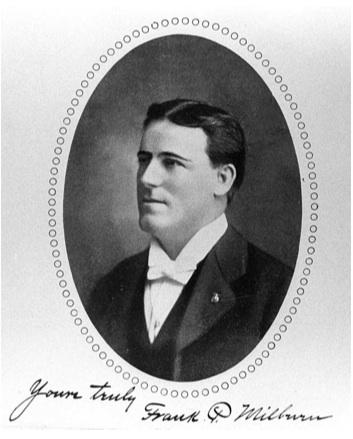

Over the past few years I've become quite intrigued by architect Frank Milburn, a prolific mid-Atlantic/southeastern architect who, nearly-anonymously (at least in contemporary terms,) might have been preeminent architect of the New South during the 1890s-1920s. Despite this prominence, he seems nearly forgotten. There have been two scholarly articles examining the work of Milburn (with and without his partner Michael Heister.) One is a 1973 article by Lawrence Wodehouse, which provided a good rejuvenation of Milburn's existence, even though the parts that most interested me - a list of Milburn's structures in Durham, seems riddled with errors. The other, more recent article appeared in Winterthur Portfolio in 2005, by Daniel Vivian. It's an excellent article - if you have academic access to such things, I recommend it highly ("The Practical Architect.") Aside from the Durham-specific view, I have little to add to the overall analysis of Milburn's career and legacy - since it is not publicly available, I will try to summarize the essence of it.

Both Wodehouse and Vivian continue the image rehabilitation of southern commercial / institutional architecture, which was often eschewed by the architecture establishment for reasons that had less to do with architecture than with disdain for all-things-southern, and a certain view of New South cities as crass upstarts and Old South cities as permanently antebellum relics. Thus the enduring image of southern architecture became the 19th century plantation house, feeding (from the point of view of someone who grew up in the deep south) northerners' odd-but-persistent fascination/obsession with the 'romanticism' of the 'Old South.' (Witness the enormous popularity of the cinematically progressive and humanly regressive Birth of a Nation - which, with its incredibly offensive storyline about the scourge of free African-Americans, and the sanctity of the Klan - remained the highest grossing film of all time from 1915 to 1921, and the slightly more subtle Gone With the Wind, which held the box office record for 34 years, until being displaced by, ahem, "The Exorcist.") Unfortunately, the ignorance of the establishment helped contribute to the ultimate devaluation of much southern commercial/institutional architecture, and its eventual destruction.

By the 1880s, New South cities such as Durham, Atlanta, and Charlotte, as well as Old South cities such as Charleston, Savannah and New Orleans, had begun to recover enough from the war and reconstruction to build / rebuild new economies. The demand for new courthouses, banks, train stations, schools, office buildings, theaters, and the like meant ready commissions for architects - the fits and starts with which much of the southern economy grew meant that private-sector work was not always steady or predictable.

I'll quote Vivian on the early development of Milburn's career:

Milburn was born December 12, 1868, in Bowling Green, Kentucky, he was the son of Rebecca Anne Sutphin and Thomas T. Milburn, a builder. He studied at Arkansas Industrial University in Fayetteville, Arkansas, from 1882 to 1883 and then returned to Kentucky, where he spent six years working with his father. Thomas Milburn enjoyed a strong reputation throughout central Kentucky. In the 1870s he designed and built courthouses in Rockcastle, Wayne, and Russell counties, and for most of the following decade he concentrated on small commercial and domestic projects. In 1888 the father-and-son team began building courthouses in Clay and Powell counties. Thus, by the time he reached his early twenties, Frank Milburn understood the fundamental stages of the building process, from the preparation of plans and specifications to the procurement of materials and actual construction.

Vivian concisely describes the path that would contribute to Milburn's later treatment by the architectural establishment - specific architectural education, licensure, and the like are relatively recent innovations - as with other institutions that successfully created standards, academic rigor, and barriers to the entry of competitors (like medicine) during this period, architecture began to shift from a mentorship- and practical-focused model to a academic model in the late 19th century. Milburn, unfortunately, was born too late to be accepted into the pantheon on the basis of his work alone, as he had contemporaries who had attended the early prominent architecture schools.

In 1890, Milburn established a practice in Kenova, WV - but he would move throughout his career to the place offering the highest volume of work at the time. Milburn earned commissions for courthouses early on, likely from connections made during work with his father. The volume of his work - meaning both commissions sought and earned - was extraordinary throughout his career; he produced designs, on average, for 25 to 55 new buildings per year throughout his career. He moved to Winston(-Salem) in 1893 to commence work on the Forsyth County Courthouse. In 1896, he built the Mecklenberg County Courthouse, and in 1900, he moved to Columbia, SC and completed the South Carolina statehouse in 1903. He produced standardized designs for smaller county courthouses, with variations that could be added for distinction.

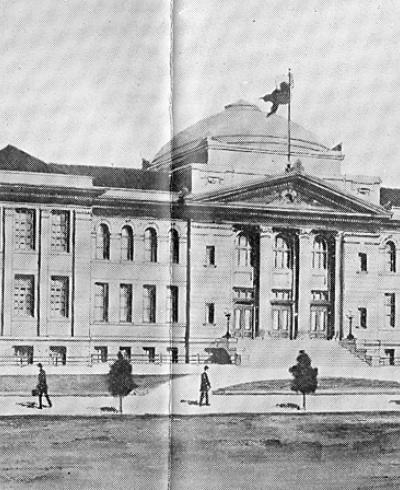

Forsyth County Courthouse, 1896

Mecklenburg County Courthouse, 1897

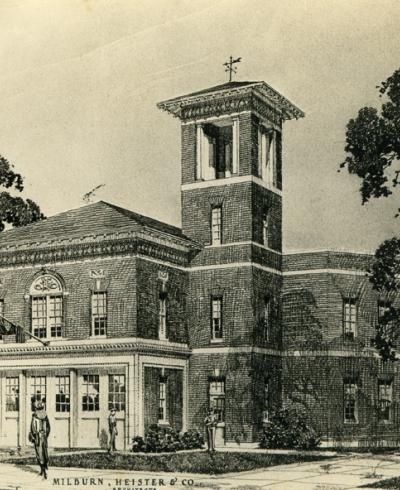

Milburn was one of the early pioneers of advertising his work widely - his promotional booklets are available on the ever-awesome archive.org - you'll have to search for various combinations of frank p. milburn, milburn, milburn and heister, etc. to find all that are available.

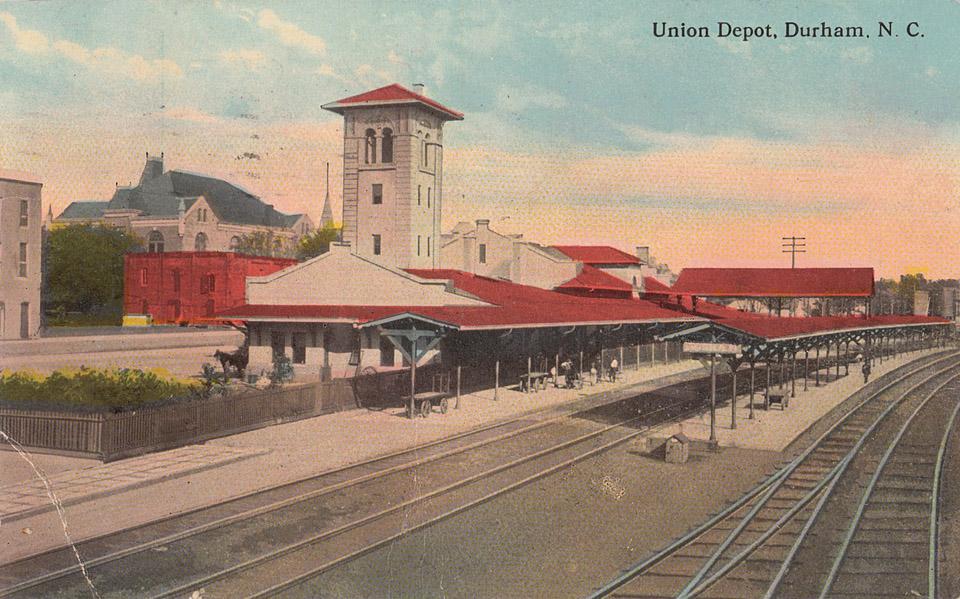

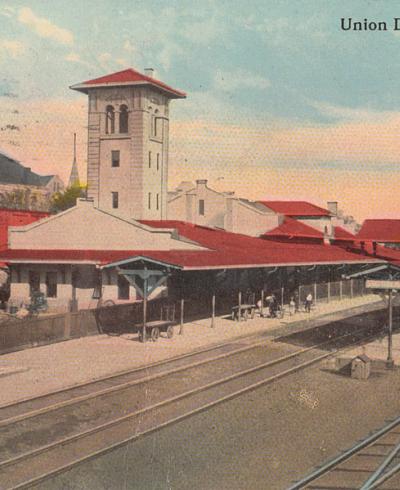

By the early 1900s, Milburn had become the official architect for the Southern Railway, and a bevy of train stations followed. This would be Milburn's first foray into Durham, with the construction of Durham's Union Station in 1905.

Durham Union Station, ~1910.

Even more dramatic station work - such as the tragically demolished Savannah, GA Union Station would follow.

Union Station, Savannah, GA, 1902

Southern Railway station, Knoxville, TN, 1905

Vivian notes that although contemporary press repeatedly praised his work, he was largely ignored by the nascent architectural establishment:

Although contemporary accounts generally praised the aesthetics of his work, he failed to attract the attention of the national architectural press. Milburn's name was conspicuously absent from the pages of the July 1911 Architectural Record, a special issue on southern architecture that featured work by architects in cities such as New Orleans, Memphis, and Atlanta as well as buildings designed by northern architects for southern markets. Nor was Milburn mentioned in Fiske Kimball's article “Recent Architecture in the South,” which appeared in the same publication in 1924

UNC made significant use of Milburn as well - I haven't attempted to account for all of the structures on UNC's campus designed by Milburn, but the YMCA, the President's house, and the Carnegie Library are some notables:

President's House, 1907

Carnegie Library, UNC, 1910

In 1906, Milburn set up a more permanent home for his practice in Washington, DC. He had hired Michael Heister in 1903, and by 1909, the firm was known as Milburn and Heister.

The firm's work, already copious, increased rapidly after the move to Washington, DC. The description of their office gives a sense of the volume:

The firm employed a dozen draftsman on average and as many as eighteen during periods of peak demand. By 1912 it occupied a suite of offices that filled the sixth floor of an office building in downtown Washington, D.C., and included drafting and reception rooms, an estimating department, individual offices for Milburn and Heister, and a private workroom.

The firm began to attract commissions for large Federal office buildings in Washington, including the ten-story Interstate Commerce Commission Building (1912), the eleven-story Department of Commerce Building (1912–13), and the nine-story Department of Labor Building (1916–17). The firm's work in DC was extensive - so much so that Milburn's obituary attributed half of the buildings in the business district to his firm's designs.

World War I Victory Arch, Washington, DC

Lansburgh's Department Store, Washington, DC.

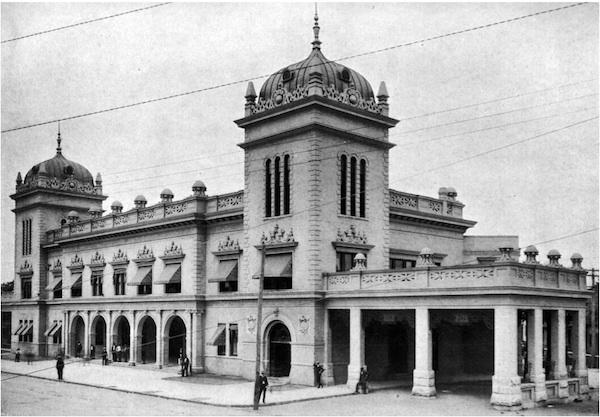

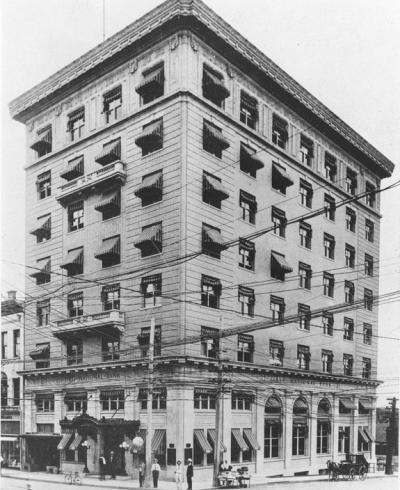

Independence Trust Company Building, Charlotte, NC - built 1908-1909.

The prolific period from 1909-1926 represented the peak of Milburn and Heister's contributions to the Durham, NC landscape. Although the central Milburn & Heister Office was located in Washington, DC, and they continued to execute work throughout the mid-Atlantic and southeastern states, Milburn's son, a UNC and University of Pennsylvania architecture graduate, T. Yancey Milburn established a "Durham Office" in 1920 and built his own home on Vickers Ave.

Many of the Milburn and Heister buildings remain, in that same anonymous way, some of Durham's most iconic historic buildings, and it seems to speak to the overall quality of the architecture that, despite Durham's hell-bent destruction of its built environment over the past 50 years, most of M&H's structures remain standing: (in chronological order)

Union Station - Built 1905 (demolished 1968)

First National Bank Built 1913.

First Presbyterian Church - built 1916 (one of three buildings demolished 1963)

Durham County Courthouse Built 1916

Durham High School Built 1922.

(Original) Hillside Park High School Built 1922.

T. Yancey Milburn House Built 1922.

Alexander Ford Motor Co. - Built 1924.

Lincoln Hospital Built 1924; Demolished 1983

Masonic Temple Built 1924.

Fire Station #1 (the second) Built 1924.

Durham Auditorium (Carolina Theatre) - 1926

City Hall (remodel of 1906 City High School. Built 1926. Still standing, but ceased being used as city hall in 1975, remodeled in the 1980s for use by the Durham Arts Council.

King's Daughters Home. Built 1926.

McPherson Hospital. Built 1926.

Of these, two structures have been demolished (Union Station, Lincoln Hospital,) two are extant but seriously threatened: (McPherson Hospital and the original Hillside Park School,) and one is threatened by a stalled renovation - the Masonic Temple building.

Milburn's health deteriorated in the early 1920s, and in 1925 T. Yancey Milburn left Durham to oversee the main office in Washington, DC. In September 1926, Frank Milburn died of a heart attack in Asheville, NC at age 56. Obituaries widely praised the architect and his prolific contributions to the cityscapes of the south and mid-Atlantic.

The firm atrophied after the death of Frank Milburn - fewer and smaller commissions came to fruition, and the firm folded in 1934. Yancey Milburn worked for the WPA and would later return to Durham for the remainder of his life.

The reputation of the firm, and knowledge of its body of work faded quickly into obscurity. Vivian notes that only 4 of Milburn's 15 major buildings in Washington survive, and "recent guidebooks to the city's architecture" fail to mention his name.

Even the few cataloguers of Milburn's architectural legacy struggle to properly account for his work. Wodehouse and the Durham Architectural and Historic Inventory erroneously states that Milburn and Heister designed the Hope Valley golf course clubhouse, which was designed by Aymar Embury, II. Yancey Milburn acted as "Resident Architect" - meaning that Embury lacked an NC architectural license, so TY Milburn reviewed and stamped the plans. Wodehouse also erroneously attributed the Unity Monument at Bennett Place to Milburn, and failed to include Union Station in his body of work. The excellent NC Architects site at NC state does a better job for his NC work, but still is incomplete.

I find the examination of Milburn's work interesting for a few reasons - one of them is that Durham, once home to the Milburn and Heister branch office, boasts a large remaining collection of M&H designed structures - perhaps the largest of any city - I don't know. Secondly, I think Milburn's reputation suffers from a few biases: the aforementioned 'southern backwater/bizarre northern romance of the antebellum' bias, and the bias of the architectural establishment. It's the latter which I find most informative in thinking about our modern view of architectural success; I am by no means a professional architectural critic, however one becomes such. But the tendency towards rewarding inventiveness and sculpturesque push-the-envelope designs in the architectural world seems to be one and the same with the world that would leave the work of a Frank Milburn mostly unrecognized. Many of his buildings were solid and beautiful, but they weren't Frank Lloyd Wright new-and-different. I'm not sure that this ethos has changed, to the detriment of solid, beautiful buildings on our streets. I'd take a building designed to be beautiful and functional in a given context any day over some Frank Gehry piece of deconstructivist AutoCAD-on-overdrive. But if a young designer wants to win an AIA award someday, what kind of work should they aspire to?

It will be interesting to see how 30-years-on history treats Durham's current recession-era boomlet in civic buildings: the DPAC, Durham Station, the Human Services complex, and the Justice Center - the first designed by Szostak design, and already award-winning, the middle two designed by the oft-awarded Freelon Group, and the last designed by O'Brien Atkins. I don't pretend to know, but I know how most of downtown Durham's new construction of the last 40 years is regarded, although it was considerably fawned over at the time.

In the interim, we can recognize that we boast a fine collection - perhaps the most intact collection of, to quote Vivian's dual meaning, a very 'Practical Architect's' work for its solid beauty, and for its significant contribution to what constitutes the notable built environment of Durham.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.