36.01068085, -78.891849121796

This elegantly appointed house was built for Nathan Dexter “Deck” Holland and his wife Lula in 1924. The architects are believed to be James and Garland Rose of Durham. At the time of its construction it was beyond the city’s northern limits in the stylish new automobile suburb, “Duke Park.” The neighborhood was laid out by Brodie L. Duke’s Duke Land and Improvement Company. The grand new house expressed Deck Holland’s optimism for the future. Sons of a carpenter, Deck and his younger brother Carey founded Holland Brothers Furniture in 1902. They nurtured the business for twenty years until it was Durham’s finest furniture store. In the 1920s, Durham was growing and business was booming. The brothers expanded their furniture lines to include stoves, appliances, and floor coverings. Their store on Chapel Hill Street was too small so they built a much larger, three-story building spanning the block between Holland and Foster Streets downtown.

Deck Holland had a flare for home decoration. He was a consummate salesman. The newspaper said of him, “[I]t is safe to say that his courteous and pleasing address has proved a winning card in drawing innumerable patrons....” Secure in what seemed a bright business future, the Hollands spared no expense in their new home. It would have an elegant, modern design by Durham’s best architects - high ceilings, commodious rooms, and a porte cochere. rich moldings and hardware, and expensive materials, central heating, appliances, and ample baths. Of course, the house would be furnished with the best articles the trade had to offer. Deck would see to that.

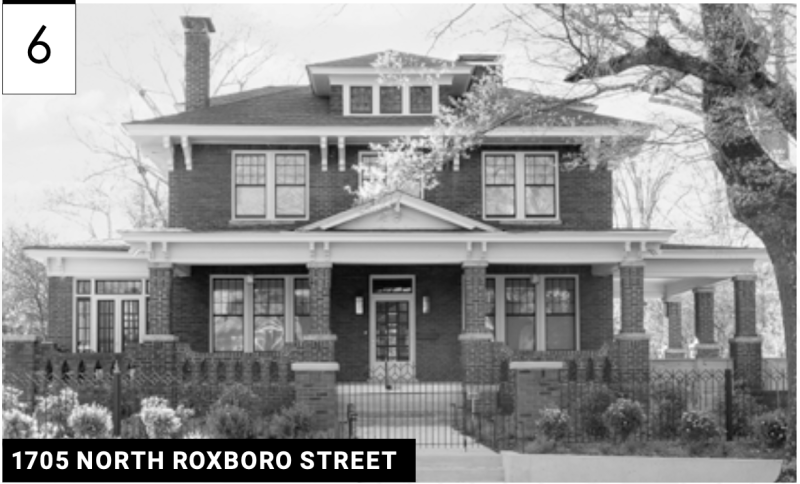

In its essential form, the house draws from the Prairie Style, but it displays elements of the Craftsman and Colonial Revival styles as well. The main pile of the structure is capped with low hipped roof with broad overhangs and hipped dormers common with Prairie houses. The upper overhangs are supported by pairs of exaggerated hammer braces typical of Craftsman houses. Across the front of the house is a deep front porch supported by double brick piers. The brackets at the porch cornice are stylized scrolls. Note the granite copings and window sills – expensive stuff, cut to fit. At the top of each pier are the brick “straps” favored by Prairie architects. On the lower level, trios of double-hung

sash windows balance on the fulcrum of the central doorway. The widow openings on the upper level are also strictly balanced. The porte cochere on the north side of the house is balanced by the sunroom extension on the southern side. Above the door, atop the cornice of the porch, is a shallow colonial pediment.

The house is clad with hard- fired, wire striated brick. The color ranges from shades of deep red to green and dark gray. Note the dark mortar in deeply raked joints. This is a Rose and Rose trademark. The same brick is used in the balustrade around the porch.

Originally, the front door gave entry into a large formal living room that ranged to the left. The ceilings are ten feet high. At the tops of the walls are elaborate moldings. Note the severely classical fireplace. The mantle is supported by fluted and fileted Tuscan columns and an architrave with tri-glyphs and even guttae. French doors once joined this room to a music room on the right. Today, few guests enter the home from Roxboro Road and the current owners have shifted the public spaces toward the rear of the house. They have added a colonnade which has the effect of extending the central hall the entire depth of the house and making the living room a more defined and intimate space. Everywhere in the house, the owners have endeavored to preserve and restore unifying elements like original floors, moldings, doors, and casework. It was necessary to replace many of the windows, but the new true- divided-light windows have the same nine and six over one light pattern as the originals. Throughout the house, fireplace surrounds and their coal grates and covers are original. The original many-prismed chandeliers were saved, restored and reused.

For the most part the owners kept the basic room spaces although their functions have changed here and there. The main exception to this is the elimination of the original butler’s pantry/breakfast nook that originally joined the kitchen to the dining room. Even here, however, a special effort was made to save the pantry’s cabinetry for re-use in the new built-in hutches in the dining room. The diamond-paned glass cabinet doors are another Rose and Rose favorite.

Where formerly the kitchen was a workspace shut away from the rest of the house by spring-loaded swinging doors, today an enlarged opening joins the renovated kitchen directly to the formal dining room. Note how the new oak floors in the kitchen weave seamlessly with the original floors in public and family spaces. In the 1920s, the original kitchen floors would have been clad with linoleum. Floor coverings were a Holland Brothers specialty line.

The stair in the house is located where the entry from the porte cochere and the central hallway meet. The stair is original. Its colonial spindles and rail spiraling to the newel are just as they were when the house was new. The landing where the stair turns receives soft light from abundant nine- over-one north-facing windows. Originally there were four bedrooms upstairs opening onto a hallway running across the house transverse to the hall downstairs. Each pair of bedrooms was originally served by Jack-and- Jill bathrooms. Today one of these bedrooms and its bath have been used to make a master suite. The ghost of the bedroom doorway is barely visible in the west wall. The quarter- sawn pine floors upstairs are original.

When the current owners purchased the house in 2019, it was a wreck. Everywhere exterior woodwork was rotting. Soffits and window frames were decayed. Water was coming through the roof to warp and damage porch ceilings. Ivy and other vines were slowly claiming the rear of the structure. Inside, the house was grim. Water infiltration had caused plaster walls and ceilings to split, crumble, and collapse. The basement areas were damp. There was still a load of coal

in the basement bin. It was a house only a preservationist could love. Fortunately, the current owners, experienced in restoring old houses, saw the beauty through the decay.

To tackle these problems, the owners assembled an accomplished team of designers and contractors. The architects for the project were Linton Architects of Durham. Roux MacNeill was the interior designer. Kennedy Building Company was the general contractor. Landscaping for the large lot was done by Garden Environments. The owners and all the participants stressed that the project to bring the house back was a collaborative effort.

In addition to repairing the pervasive damage and updating systems, the team had to overcome the problem of reorienting the interior of an historic house from the front to the rear. When the house was new, its public face was toward Roxboro Street. Guests parked on the street and approached the house from the sidewalk. The front door gave entry to the formal living and dining areas of the house. The family entered the house from the porte cochere on the north side of the house which provided equal access to the public and family areas. The rear of the house, off the alley behind, was given over to the kitchen and service rooms. Also, the sloping lot put entry points on this side at the basement level.

Over time, as Durham grew, Roxboro Street changed. Instead of a country road at the edge of town, it became a thoroughfare. In an increasingly automobile age, traffic increased. On-street parking became impossible. Even turning into and out of the driveway became a difficult affair. It was easier and safer for everyone, family, guests, and servants, to enter the house through its utility and service areas from the alley at the rear.

To tackle this problem in a way that respected the historic design of the house, the project team redesigned the rear of the house and the yard. While the basic structure of the original house was left alone, the back yard was terraced upward beginning with new parking areas connecting to the alley and lifting upward through three levels of outdoor spaces in a series of yards, gardens, and decks. These contain a modern pool, pergola, and seating areas with southern exposure. Where the basement once contained utility spaces, the laundry and servants’ rooms, there are now living spaces. There is a bedroom, a bar-kitchenette, and a den-television space. The foundation wall on the south side was opened up to join this new space with the garden and pool area. To accomplish this, it was necessary to add a steel beam to carry the weight of the house above. Light now pours into a space that was originally dark. The new and the old are wonderfully blended together. The brick is exposed. Here and there old plasterwork has been preserved. The original laundry sink has been reused.

Upstairs, the historic formal rooms at the front of the house have been preserved, but the service and family areas at the rear have been converted into more informal reception and family spaces. Rather than redo these rooms in a false historic decor, these new spaces are consciously modern. Joining the house to the outside spaces is a new sunporch. In fair weather, the glass wall opens accordion fashion to connect directly with the outdoors on the quiet side of the house. The large, original downstairs bedroom has been converted into a new, informal living room. The windows and fireplace have been preserved to recall the room’s purpose, but it is now opened up to the central hall and to the large modern kitchen opposite. By opening interior walls, the kitchen has become the hub of the house, communicating to historic formal spaces at the front of the house and the new informal rooms at the rear.

The Hollands' house was built in a season of prosperity and optimism, but that season did not last. The Great Depression hit the Deck Holland family particularly hard. The furniture business dropped off as new home construction stopped and discretionary spending shrank. Deck Holland was over extended. In 1932, he borrowed $5,000 and secured the loan with his new home. He could not make the payments and in 1933, the bank foreclosed. Deck’s brother Carey Holland came to the rescue. He bought the house in the foreclosure sale and allowed Deck’s family to continue to live in it. By 1940, Deck Holland had sold his share of the business to Carey as well. Holland Brothers became the C. T. Holland Company and Deck became his brother’s employee. During the Depression and war years, the household swelled as the Hollands’ grown children, Alton Holland and Mildred Lea and their families, moved in with their parents. A servant, Emma Edwards, also lived in the Holland house.

In 1953, Carey Holland conveyed the house to his niece, Mildred for her life and then to Deck’s other family when Mildred died. The family continued to make their home in Roxboro Street house until the late 1950s when, in rapid succession, Alton Holland, Deck Holland and Lula Holland all passed away. In 1963, the family sold the house to Kyle and Kimberly Bruce. Kyle Bruce worked in the water resources division for the city. His family lived in the house until 2018.

Through a strong commitment to preservation, a thoughtful blending of old and new, and the close collaboration of new owners and their team of designers and contractors, the beautiful Holland House has been saved.

Comments

Submitted by Seeman1985 on Wed, 6/28/2023 - 10:00am

Been drooling over this house since 1984. Very happy that it has been saved and put back into family use.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.